Victor F., a 2018 Christianson Fellow, spent eight months in the Dominican Republic as a volunteer with the Mariposa DR Foundation, an organization devoted to empowering and educating young girls and young women to end generational poverty. He reflects on the powerful lesson he learned from his female students.

As a volunteer with the Mariposa DR Foundation, I taught self-defense (I have a black belt in Karate), dance, and English. I also utilized my professional experience as a college admissions counselor to prepare the girls to attend United World College—a conglomerate of international schools around the world that shape leaders who care deeply about cross-cultural understanding—and similar institutions.

Passionate about education, I knew I wanted to perform service abroad in this field, but not in the Dominican Republic. A rough childhood in the country shaded my perception. It would take the girls of Mariposa to change how I viewed the country and myself.

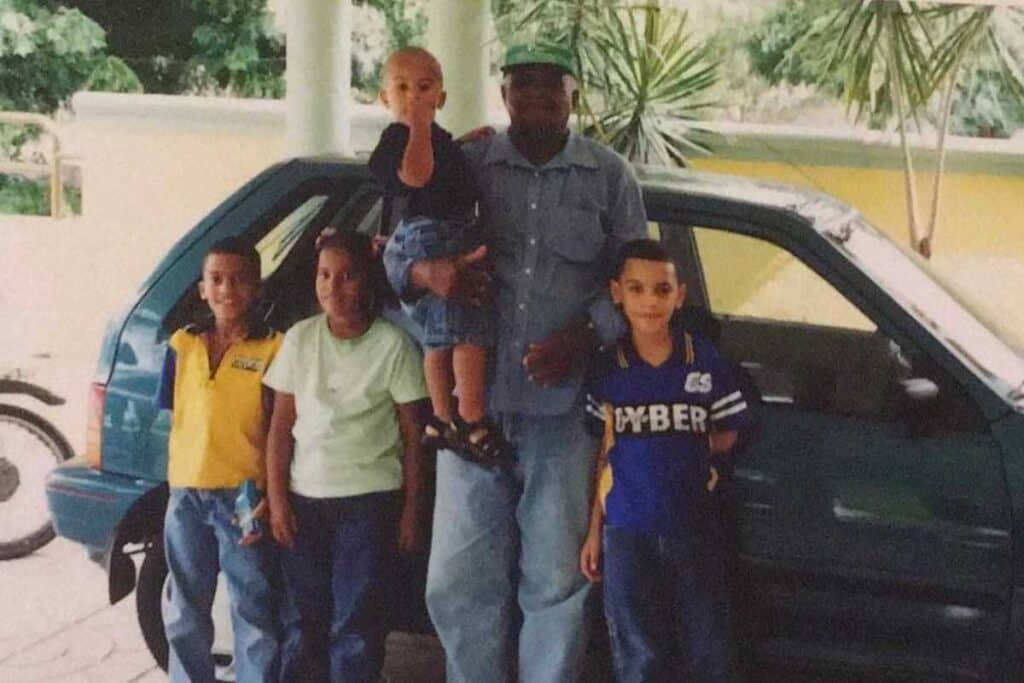

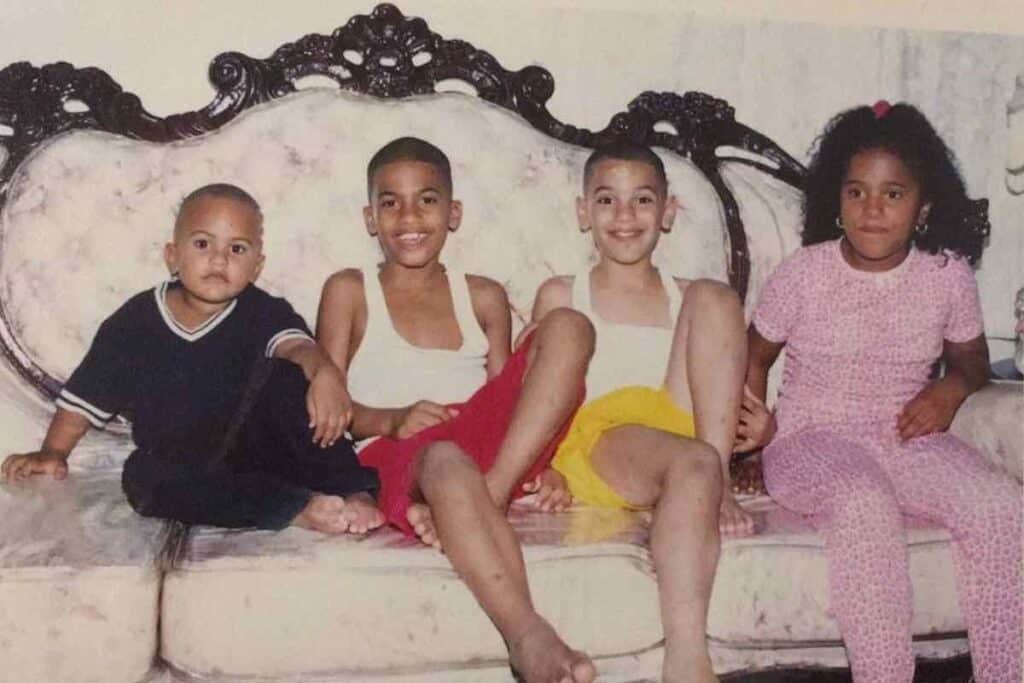

Rough Beginnings in the Dominican Republic

After living in Puerto Rico and the Bronx, my father sent me to live with his mother-in-law in the Dominican Republic when I was six. She was a strict woman with rigid expectations of my siblings and I. We met severe punishments if we deviated from her rules and expected behavior.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

During the seven years I lived in Azua, Dominican Republic, I was taught that being “Dominican” meant to dislike Haitians and anything associated with blackness. It meant that boys like me, who cried and wanted love, would not become capable Dominican men. I learned that if someone hit me, I had to hit back. If someone slighted me, I had to slight them.

I left the Dominican Republic at age 13 with a ruthless edge that veered its ugly head whenever I felt threatened.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

An Opportunity to Return

After earning a Princeton in Latin America fellowship (PiLA), which places recent college graduates in service fellowships with non-profits and other organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean, I let PiLA know that I preferred to not be paired with an organization in the Dominican Republic.

This changed when I learned about the Mariposa DR Foundation. Julia Alvarez, who is Honorary Chairwoman of Mariposa, was closely tied to my undergraduate university (Middlebury College). Like any young Latino raised in the U.S., I knew her books, but also had the privilege of interacting with her several times. She recommended Mariposa, as did several of my friends who’d visited the organization.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

It was hard to get to the Dominican Republic—financially and emotionally. Luckily, a Christianson Fellowship from the InterExchange Foundation promised some financial stability. I was nervous, though, wondering if returning was really the right emotional choice.

When I arrived in September, it felt exactly like it did the first time when I was a child. It was sunny, hot, and humid—the type of heat that triggered my asthma. There was also something in the air that I recalled, something that made you feel alive. The merengue and salsa songs in barbershops, the older folks yelling at each other in the streets, the chancletas (flip flops)—all felt familiar.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

Slowly, I recalled the constricting masculinity standards and the “othering” I felt for being part Puerto Rican and identifying as queer. The locals knew who was part of the community and who wasn’t. That “something in the air” started to suffocate me. Then, upon meeting the girls at Mariposa, I quickly realized I would have to earn my stripes with them.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

For the first two weeks, I came home stressed every day. I worried that the whole experience would revolve around being read as a “rich foreigner.” The public drivers calling me boricua (Puerto Rican) and venezolano (Venezuelan) on the guagua (bus) slowly wore on my nerves. But I couldn’t back out of this experience; I had nowhere to go and no parent for support.

The Mariposa Girls Help Shift My Perspective

What eventually changed was my relationship with the girls at Mariposa, and, soon after, how I saw myself and this country. The girls and I started to connect and I realized how much they wanted me to be here. They were curious about my Puerto Rican culture and some were amazed that I majored in Japanese—I ended up starting a Japanese-language study group because so many were interested!

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

One of the girls asked me to choreograph her quinceañera (celebration of a girl’s 15th birthday) dance. Two others wanted me to choreograph their senior high school dance. I often bumped into some of my eight and nine-year-old students on walks with their siblings and parents, and they never failed to run towards me for a hug.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

During my volunteer stint, I attended two of my student’s quinceañeras, choreographed two dance performances, and found a new appreciation for the emotional investment teachers put into their students—it feels like I adopted 40 daughters and 60 younger sisters. They have changed how I see myself and the Dominican Republic.

They remind me that Dominican culture also means to love life and to not always take everything so seriously.

At Mariposa, we were encouraged to incorporate atención plena (“mindfulness”) into our classes. I reminded the girls to be mindful, to think and live in the now. To take a deep breath when they’re not the first one to go or when they lose a game or competition. The girls also taught me atención plena—to stop taking life so seriously, to let go of the past for the now. Thanks to them, I’m living life a little more for the present.

Image courtesy of Victor Filpo

This focus on mindfulness made me think about the man and adult I was to the girls. I stopped to remember the patience I must have with the people I love, despite the emotional intensity of a situation. I breathe and think about the kind of impression I want to leave in that person’s life.

A nine-year-old Mariposa girl, who reminds me very much of myself as a child, wrote me a letter recently:

Victor is very important for me since I’ve arrived at Mariposa. You were very important. I love you forever. He supports me in everything. I have fun with Victor. I love you Victor.

This reminds me to let go and just be—to forgive the younger Victor and my hard experiences in the country so I can enjoy the present moment.